- Home

- Susan Calman

The Day She Saved the Doctor Page 2

The Day She Saved the Doctor Read online

Page 2

‘Golden Delphonian mega-dollar. Solid gold. Now talk.’

The man’s hand shot out and grabbed the coin. ‘Well, it’s been happening all over – people turning up blind. At least three others I’ve heard of, could be more. Probably looked at something they shouldn’t have. Weak minds, women have. Can’t handle stuff.’

‘I’ll give you weak minds –’ Sarah began, then felt the Doctor give her arm a restraining squeeze.

‘Do you know who these others are? Where they live?’ he barked at the stallholder, who looked slightly alarmed at the ferocity of the Doctor’s voice and took a step back.

‘Well, I might do,’ he began, clearly trying to regain control of the situation. ‘If I thought hard.’

Another Delphonian mega-dollar landed in front of him.

‘Yeah, I think I can remember.’ Names and addresses spilled from his lips. Then, his fingers stroking the two huge coins, he added, ‘For another one of these, I could even take you there.’

‘We can find our own way,’ said the Doctor. His eyes swept the stall. ‘I’ve already paid more than the information was worth. In fact, I think I’ve paid enough for all these birdcages too …’

As the stallholder watched in dismay, the Doctor moved along the stall, opening all of the birdcages and shooing out the little creatures within.

Sarah clapped her hands in delight, ducking as a cloud of chaffinches swooped over her head.

‘I don’t like things in cages,’ the Doctor said.

The Doctor and Sarah went to visit the homes of the people the stallholder had named: Lucius Sestius, a silk importer; Gaius Helvius, a grain trader; and Manius Salvius, an ivory supplier. At every house they found a blind woman – each time, the merchant’s wife – and all their stories were the same: pain, then a sudden awakening to blindness, with no knowledge of what had happened in between. Each woman had come to herself alone, frightened and sightless, somewhere in the streets of Ostia, and on her arrival home had discovered she’d been gone for days.

‘Could it simply be an illness?’ Sarah suggested, as she and the Doctor walked back towards the marketplace. ‘There are diseases that can cause blindness, aren’t there? Measles and things like that? Or – oh! I know! There’s river blindness. Flies that live near water pass that on, and Lucilla did say she was near the harbour when she became unwell.’

‘An impressive fly, to ignore everyone who works at the waterside in favour of a few merchants’ wives.’

Sarah shrugged. ‘All right, I didn’t claim it was plausible. So let’s accept that someone’s deliberately targeting these women. Who, or what? And why? We don’t have a lot of leads.’

‘We need to work out who the next victim could be,’ said the Doctor.

‘Okay, so let’s find other women who are in similar positions to the previous victims,’ Sarah said, eager to start digging and already drawing connections. ‘We know they were all married to Ostian merchants – and, going by their houses and their clothes, pretty successful ones too.’

‘I know just the person to ask,’ said the Doctor.

As soon as they were back in the market, the Doctor headed straight for their old friend, the stallholder. It would be a lie to say the man looked happy to see them.

‘You again,’ he snapped.

‘Ah, good, you remember me,’ said the Doctor.

‘How could he forget you, Doctor?’ Sarah said with a smile.

‘Doctor? Doctor! Well, that makes sense. A foreigner.’

‘Are you a foreigner, Doctor?’ asked Sarah, wide-eyed and mock surprised.

‘Ah, most of the doctors in Ancient Rome were Greeks, you see,’ the Doctor explained. ‘So were most of the philosophers and mathematicians, of course, so, well –’ he smiled at the stallholder – ‘it’s not that surprising that I’d be mistaken for one.’ He pulled an empty box from under the stall and stood on it, one hand holding his coat lapel and the other stretched out to an imaginary crowd, as he declaimed, ‘I think, therefore I am the sum of the squares on the other two sides. Take 3.14159265 tablets before meals with a glass of water.’

Sarah burst out laughing, and the Doctor climbed off the box. The stallholder didn’t seem to find it quite as funny, but he sulkily gave the Doctor the information he asked for. Titus Fabius, Lucius Sestius, Gaius Helvius and Manius Salvius were undoubtedly some of the most powerful and important merchants in Ostia; according to the stallholder, there were only four others who could come close to matching them. He gave the Doctor their names and addresses.

‘You take two. I’ll take two,’ the Doctor said to Sarah. ‘Talk to the wives, find out their plans for the next few days. See if anything leaps out at you. See if they have any connection to the other women, besides being merchants’ wives. I’ll meet you back here.’

At the first house Sarah visited, she was granted an audience with Aulus Pumidius’s wife, Marcia. As they sat drinking honeyed wine, Sarah did her best to explain the situation. Marcia was older than the other women they’d met that day, and didn’t seem inclined to take Sarah’s warnings seriously.

‘Yes, I’d heard that Lucilla and the others had met with misfortune – my slaves keep me well informed – but are you seriously trying to tell me I might be in danger too?’ she drawled, incredulity clear in her voice. ‘Sweet of you to advise me, but I think I’ll take my chances. Besides, my husband is away in Carthage, carrying out some very important business negotiations, and I am kept extremely busy in his absence. I’ve no time to go gadding about Ostia, waiting for someone to strike me blind.’

Sarah persisted. ‘We don’t know what happened to the other women. Whatever it is could just as easily happen to you here, at home.’

Marcia rolled her eyes. ‘I’m surrounded by slaves at all times. Nothing and no one can get in to my house without my knowledge.’

Sarah realised Marcia wasn’t going to take the threat seriously, no matter what she said, so she took a different angle. ‘Do you know the four victims socially?’ she asked.

‘Yes, we meet from time to time.’

‘Well, can you think of anything they all have in common? Perhaps something that’s relevant to you too? Apart from the fact you’re all married to merchants.’ This was just the sort of thing Sarah enjoyed: interviewing sources, searching for that tiny scrap of information that might make a story, that little clue that might link one thing to another and bring about a breakthrough.

‘Apart from our husbands, and apart from the fact we are all women, no. I can think of nothing.’

All women. A switch suddenly flicked in Sarah’s mind. It was probably nothing. No more than the merest hunch … but a journalist had to follow her hunches. ‘Is there a temple of the Bona Dea in Ostia?’ she asked.

‘Yes, down by the harbour. Why do you ask?’

‘It’s just that it’s the only place I’ve heard of here that’s for women only, and as you say all the victims have been women,’ said Sarah. ‘Sick women. Women who might be taken to a place of healing.’

‘Oh, that seems very far-fetched,’ said Marcia, with a supercilious air. ‘More wine?’

‘No thanks,’ said Sarah, still caught up in her hypothesis. ‘I’d better be going. It probably is far-fetched, but I think I’m going to ask a few more questions of the other women.’ She drained her cup and stood up. ‘Thank you for your hospitality. And please – stay safe.’

Meanwhile, the Doctor was finding Caelina, the wife of Sextus Icilius, an ivory merchant, much more willing to talk. In fact, he could barely get her to stop talking. She was half his height, twice his width and full of pity for the four women who had been blinded.

‘That poor Lucilla,’ she said. ‘And to think I was only sitting chatting with her the other day and she had no idea what the gods were about to visit upon her. And with her just having had a little boy too. Imagine never seeing his chubby little cheeks again! I don’t like to think of it, that’s a fact.’

By this point, the Doctor ha

d been listening for twenty minutes to tales of all the misfortunes that had been visited upon Caelina, her children, her friends, her friends’ children and pretty much anyone else she’d ever come across. ‘You don’t know of anyone who might have wished harm to these women?’ he asked, trying to steer her back to the topic at hand.

‘There’s not a single person who’d want to hurt a hair on any of their heads,’ Caelina informed him. ‘If we were talking about their husbands, though …’

The Doctor leapt on this. ‘Someone might want to hurt their husbands?’

‘Well, not actually hurt them – I’m not saying that – but that Aulus Pumidius, he’s right jealous of the lot of them, and that’s including my Sextus. All more successful than him, and he doesn’t like it. He’d do them a bad turn if he could. But he can’t have had anything to do with this, because he’s been gone for, ooh … about ten days. Off trying to undercut someone else’s deals, probably.’

‘Aulus Pumidius? My friend’s gone to speak to his wife.’

Caelina snorted. ‘I wish your friend joy. That Marcia’s a stuck-up one and no mistake. Lording it over us at our little gatherings when she’s got nothing to be superior about.’

The Doctor’s ears pricked up. ‘Little gatherings? You and the other merchants’ wives meet up?’

‘Well, wasn’t I telling you only now how I was sitting with Lucilla just the other day? Every few days we have a little get-together – a bit of a gossip and a few honey cakes. Only with those from our own sphere of life, of course.’

The Doctor questioned her urgently, and learned that every single one of the victims had vanished shortly after one of these get-togethers – but none of them had mentioned it. Why? Were they too traumatised to put two and two together? Or was he the one who was leaping to conclusions?

The Doctor jumped up abruptly. ‘I need to find my friend,’ he told Caelina.

‘Well, good luck to you. And don’t you worry about me. I’m not going to let anyone blind me, the gods’ will or no.’

Sarah was trying to find the house of the second merchant on her list. Marcia had told her about a shortcut, but it didn’t seem to be taking her where she wanted to go. She was hardly an expert in Ostian geography, though, so she shrugged and carried on hopefully.

She winced at a twinge of pain – a brief dart across her stomach. Then another twinge, not as brief. She stumbled forward, looking for a place to sit down. As the noise of gulls filled her ears and she breathed in the smell of salt, she realised she was near the harbour. The pain was getting worse, her stomach cramping so much she couldn’t take another step. Then a hand grabbed her arm, and a familiar voice said, ‘You look ill. Let me take you to find help.’

As she was dragged away, the tiny part of Sarah that was still conscious sobbed inside her head, Not me. Don’t let me go blind. Oh please, don’t let me go blind.

The Doctor thumped his fist against the wall of Aulus Pumidius’s house. He was too late. Sarah had already left, the young slave on the door had informed him, and Marcia, the mistress of the house, had gone out shortly afterwards. The Doctor was frustrated, and he was worried.

‘Did you hear anything of their conversation?’ the Doctor asked the slave.

The boy shook his head, but the Doctor wasn’t convinced. He knew the Ancient Romans treated their slaves like furniture; it wouldn’t have crossed Marcia’s mind to keep quiet in front of this boy.

‘Come on, you can tell me,’ he said, with a winning smile, hypnotic eyes boring into the slave’s nervous ones. ‘Have a jelly baby.’

The boy shook his head again, both at the question and at the offer of the strange green sweet. ‘I dare not,’ he whispered.

‘Because you’d be punished,’ the Doctor said. ‘I understand, but I need your help. It’s critical. My friend could be in great danger, and any information you give me could save her life.’

‘They talked of the Bona Dea,’ said the slave, still whispering. He was staring down at his bare feet, as though by not looking at the Doctor he could pretend he was telling his secrets to the air. ‘The mistress put herbs in the lady’s cup. After the lady left, the mistress followed her.’

‘Thank you,’ said the Doctor. ‘Oh, and here’s something for you.’ He held out another of the golden coins. ‘For caring more about my friend’s safety than about your own. That should be enough to buy your freedom. I think you deserve it just as much as a chaffinch.’

Ostia’s temple of the Bona Dea was surrounded by a high wall. Even standing on tiptoes, the Doctor wasn’t tall enough to look over it. He walked alongside the wall until he found a gate, then gave a firm rat-a-tat. A few moments later, a girl of about ten years of age opened the gate, bowed her head and asked the Doctor his business.

‘I’m the Doctor,’ he announced. ‘I have heard that the priestesses here are healers, and since I am feeling rather poorly – a bad dormouse or rotten lark’s tongue at lunch, no doubt – I thought I’d pop in for a bit of healing.’ He gave the girl one of his most charming grins.

She bowed her head again. ‘I regret that men are not allowed within the temple, sir,’ she said. ‘But if you will wait here, I will fetch you herbs that should ease your pain.’

‘Thank you,’ he replied. ‘Of course you can’t let a man in the temple, but perhaps I could walk in your grounds while I wait? I see you have a lot of fascinating snakes slithering about in there that I’d very much like to take a look at.’

The girl shook her head. ‘I regret, you may not step inside our walls, even to examine the sacred snakes. Please wait here.’

The gate closed in his face.

The Doctor sighed. ‘Maybe I should have tried a ribbon in my hair after all.’

Sarah awoke to the sounds of an argument. She still felt weak, but the crippling pains had gone. Thank goodness. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d felt so ill.

‘What do we do with her now?’ she heard a voice say.

‘The same as we did with all the others,’ said another.

‘But she has no knowledge that we need.’

‘Maybe not, but her memory must be taken away.’

Sarah risked opening an eye. Two figures swam into focus: Marcia, the merchant’s wife, and an elderly woman in the simple white robes of a priestess. They were standing in front of – and Sarah had to blink a few times to make sure this wasn’t a fever dream – one of the most complicated pieces of machinery she’d ever seen. A machine that surely shouldn’t be anywhere within a few thousand years of Ancient Rome. So what was it doing here? But, before she could solve that mystery, Sarah’s priority had to be getting away. She glanced around for any escape routes, and spotted two doors – one on either side of the room.

Sarah shut her eyes again and considered her options. She was almost certainly physically stronger and faster than her captors, so making a break for it before they realised she was awake seemed the obvious course of action.

Sarah waited, watching the two women through nearly closed eyes, until they both turned away from her. Then she leapt up and dived for the nearest door. She was through it, she was running –

But the goddess Fortuna was not on her side. Sarah hadn’t realised until she was up and moving how weak her body still was from whatever it was that had struck her down. Poison, she now suspected, slipped into her wine by Marcia. She forced herself desperately forward, step by painful step, but the walls had begun to swim around her and she seemed to have forgotten how to breathe. She had thought she was still running, but when Marcia and the other woman grabbed her arms she realised she was actually on her knees on the floor. She decided it was definitely time for Plan B; it was just a shame she hadn’t come up with one.

Well, her escape attempt might have been foiled, but there were still things she could do. The Doctor always said that nine out of ten times evil-doers were happy to explain their plans – not necessarily for grandstanding reasons, but because putting things into words acted as valida

tion for them. Time for Sarah to put that theory to the test.

‘I like your machine,’ she said, as cheerfully as she could manage with burning needles of pain sticking into her stomach. ‘Very impressive. Did you make it yourselves?’

‘It was a gift from the gods,’ Marcia said in the same condescending tone from earlier. Sarah thought she detected a hint of sarcasm there too.

‘How very generous of them,’ said Sarah. ‘I hope the gods gave you an instruction manual. Perhaps you could explain what it does? Besides blinding people and wiping their memories, that is.’

‘Do not mock our gods!’ The priestess turned on Sarah – and Sarah saw her milky-white eyes.

‘You’re blind!’ she exclaimed. ‘This machine – whatever it does, it did it to you too.’ She made her voice deliberately soft, sympathetic, persuasive. ‘I’m sorry for mocking your gods. Tell me what happened to you. Please.’

‘Do not indulge her, sister,’ said Marcia imperiously. ‘Let us get this task over with.’

But the other woman shook her head. ‘No, it is fair to tell her what we know. After all, the gods granted me the gift of knowledge before they took my sight. I will pass on the favour.’ She turned to Sarah. ‘Child, know that I am Orbiana, servant of the Bona Dea. I will tell you of the gods’ visit to us.

‘The gods came to us in disguise, just as Jupiter and Mercury came to Baucis and Philemon. They told us that, to them, the female is the personification of knowledge, so their search for wisdom had led them here.’

‘A pity the gods have never passed on this opinion to the men of our city,’ commented Marcia, with a sniff. Despite the fact that Sarah was predisposed to dislike her – the poisoning and the imprisonment had rather coloured her feelings – she had to agree that Marcia had a point.

‘They brought with them this device,’ Orbiana continued. ‘It is a way for the gods to know the affairs of our world. They share the eyes of mortals, taking all that they have seen and sealing it forever into a crystal for the gods to consult.’

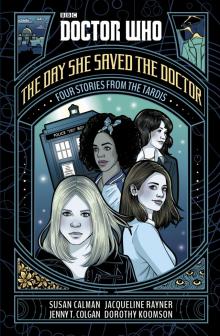

The Day She Saved the Doctor

The Day She Saved the Doctor